When my 7-year-old son was diagnosed with diabetes, I had no idea how dramatically the disease would impact our entire family.

My sweet son, Malik, was 7 when he had the flu, just as our whole family did. But he didn’t get better: He was extremely tired, constantly thirsty, wetting the bed, and losing weight (even though he wanted to eat all the time). I could explain away each of these problems, but when I saw how frail Malik looked, I Googled his symptoms, and they were classic signs of type 1 diabetes (T1D). I left a frantic message for my pediatrician in the middle of the night, which I instantly regretted: I was being an annoying mother, trying to diagnose my own son.

But the doctor walked into the exam room the next morning, took one look at Malik, tested his urine and blood, and then called for an ambulance. Malik was admitted to the ICU, where, after a terrifying flurry of activity, doctors confirmed that he did in fact have T1D.

Could Your Child Have Diabetes?

About 3 million other Americans are living with T1D and roughly 10 percent of them are children or adolescents (it was previously known as juvenile diabetes, because it’s usually diagnosed in kids). There’s no cure for this autoimmune disease, which occurs when the body does not produce any insulin, the hormone needed to convert sugar in food into energy. (T1D is different from type 2 diabetes, the more common type, in which the body doesn’t respond properly to insulin or doesn’t produce enough of it.

What Is Type 1 Diabetes?

When a child has T1D, his blood- glucose (sugar) levels must be checked several times a day. Based on those readings, he eats, modifies activity, or takes insulin to keep his glucose at a healthy level. Otherwise serious complications can develop. This is what landed Malik in the ICU: He had diabetic ketoacidosis, which occurs when your body, deprived of insulin, burns fat for energy instead, producing acids called ketones. High levels of ketones can poison the body when glucose levels are high and can lead to coma, even death.

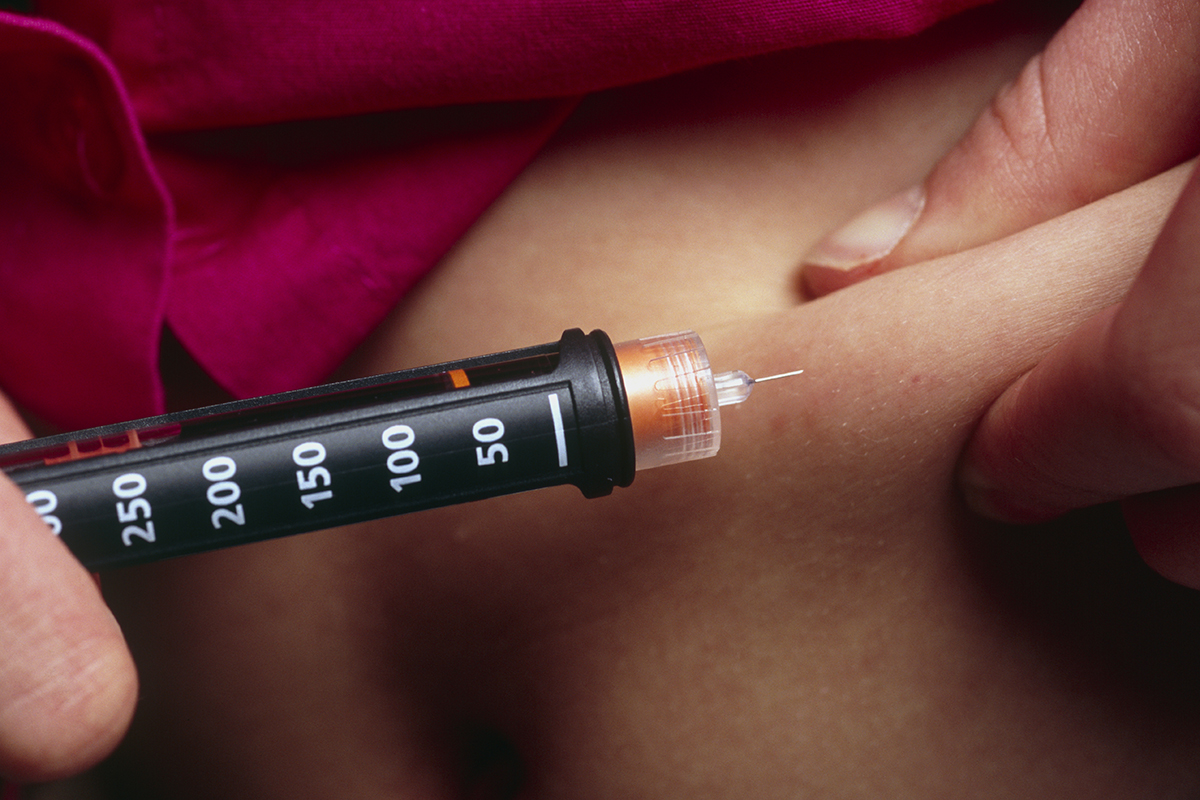

After Malik was diagnosed, the doctors, nurses, and everyone we encountered used the phrase “new normal” to describe our diabetes routine. I’m sure they thought it was somehow comforting, but it is not normal to constantly gather drops of your child’s blood. Same goes for giving your child a shot every time he eats and every night before bed. Yet we are getting used to this. My son no longer cries or struggles every time he needs a shot. In fact, I’m so good at giving shots now that I secretly think of myself as a nurse (no disrespect to actual nurses). And my husband, Lee, and I sleep through most nights now. When Malik first left the hospital last year, it was a bit like having a newborn again. We got up all the time at night to make sure that he was breathing, but we’d poke his finger and check his blood too. Now we only check him at night once a week or so.

I want to pay tribute to my son and his journey by honoring the anniversary of his diagnosis, complete with photos I’ve taken — as a professional photographer, I’ve always chronicled our life in pictures. I know it sounds odd to “honor” his condition. But I want to celebrate his life, and diabetes is part of it.

Big Changes for All of Us

We quickly decided it was not only Malik who has type 1 diabetes, but our whole family. Lee and I agreed to implement many of the necessary lifestyle and diet changes for ourselves and our two daughters as well. We were already extremely healthy as a family; I’m an organic mama and my three children have been raised on vegetables and other healthy food. Lee, who’s a former professional basketball player, has instilled a genuine love of sports in our children. It’s important to understand that type 1 diabetes is not preventable; it was not brought on by any dietary or lifestyle choices we made. Though there is a genetic link — your odds of developing T1D rise if someone in your immediate family has it — this wasn’t the case in our family. It was just bad luck.

One major change was no juice. Juice has a lot of sugar and could send Malik’s blood glucose too high too fast. In fact, he can have one small juice box only if he has a low blood-sugar reading. Juice is now “medicine” for him.

Malik had an intense fear of shots, so it was really hard for him to comprehend that he’d need four or five shots every single day. He came up with his own terminology to minimize his fear. The very word shot would cause him stress, so he decided to call it “the S-word” (very clever, in my opinion — shot is so a four-letter word). He refers to insulin as his “power source.” We’ve all honored his word preferences and his 5-year-old sister, Jasmine, is sure to let anyone know to not say shot in front of her brother. His anxiety levels have greatly decreased over this year and he can now handle hearing the word from time to time, but for me it will always be “the S-word.”

In another effort to help him, we all tried to prick our fingertips and check our blood sugar. He really loved this. I was most proud of Jasmine: She was very worried about pricking her finger; she tried several times over many months and always backed out at the last minute. Then one day, she marched into our room and announced she wanted to check her blood sugar and she held out her finger. We swabbed it with alcohol and pricked it and checked her number; she gave me a sly smile and said, “That didn’t even hurt that much.” Her brother laughed. It’s moments like those, so bizarre and yet so sweet, that keep me going.

Making Sure Celebrations Aren’t a Bummer

Diabetes is a bit like having an uninvited stranger move into your home who needs attention all the time and goes everywhere with you. It’s just a major drag. The toughest obstacles I faced as a mother this year were special occasions and holidays. I decided nothing would be different — meaning we’d still go trick-or-treating, and Santa would still put sweet treats (which were usually off-limits) in the stockings at Christmas. But first, and most important, I was determined to make my son a fabulous cake for his birthday in August.

If you’re thinking, “Cake for a diabetic?!” let me explain. I was adamant about not depriving Malik of the experiences of holidays and celebrations. So I asked his diabetes team (yup, it’s an actual team, with doctors, nurses, a nutritionist, and a counselor) for advice on birthday cake. The consensus: I could go ahead and make a cake, and if I used a substitute sweetener, it’d have slightly fewer carbs. Knowing cake was a rare treat, I decided to make a regular one — a big, cool cake with toy airplanes on top. It took hours, and I had lots of fun decorating it. Malik would wander into the kitchen to check my progress. His friends arrived and they all played in the backyard and had lunch.

The best moment was when Malik and I filled his plate and discussed the amount of insulin he’d need to take. (We always talk through this; I want him to understand too.) To get ready for cake, we checked his blood and gave him his S-word and none of his friends batted an eye or paused in the boyhood banter. But Malik said, “Mom, I really don’t feel like eating cake. Can I just have two of the airplanes?” He instinctually rejects unhealthy foods in a way he hadn’t before his diagnosis. So I let him pick out two of the toy planes and he had a couple of dried apricots instead (since he already had a shot of insulin and didn’t eat the cake, he needed some extra carbs to make sure his glucose level was steady).

All in all, we have had a year full of beautiful celebrations and experiences. A year full of blood draws and S-words. And we did it together, as a family.

Last night before Malik went to bed I asked him, “What is the worst thing about diabetes?”

He replied, rather incredulously, “The shots.”

Then I asked, “What is the best thing about diabetes?”

“No one messes with your food,” he said with a bit of a giggle, because he doesn’t have to share it.

I laughed and kissed him and realized how we truly are still so much the same.

His affable wit is intact and our rapport is rich with our shared history. We actually are beginning to create a “new normal.”

Diabetes Red Flags

The condition — type 1 or 2 — is dangerous if it goes untreated. Look for these potential warning signs.

- Unquenchable thirst

- Urinating every few hours or more frequently

- Bedwetting in children who previously had dry nights

- Excessively wet diapers for infants

- Difficulty managing diaper rashes or yeast infections

- Nausea or vomiting

- Increased appetite

- Irritability

- Drowsiness or lethargy

- Sudden weight loss

- Sudden vision changes

- Fruity odor on the breath

- Heavy or labored breathing

- Stupor or unconsciousness

4 Alternatives to Insulin Shots

Good news for kids like Malik: These methods don’t require as many finger pricks throughout the day. Parents advisor Lori Laffel, M.D., chief of the pediatric, adolescent, and young-adult section of the Joslin Diabetes Center at Harvard Medical School, explains how they work.

- Insulin pens

These injectors can be prefilled with insulin (disposable) or have replaceable insulin cartridges (reusable). The pens have easy-to-use dials for selecting the right dose of insulin. Some even come with a memory of sorts, so you can see the time and amount of the previous dose. Others can offer half-unit dosing, which is especially helpful for children, says Dr. Laffel. - Insulin pump

Many children eventually switch from injections by syringe or pen to this pager-size device as an alternative way to deliver insulin. The pump can be carried in a pocket or a fanny pack or worn on a belt. It delivers an ongoing low dose of insulin via a flexible tube attached to the body through a small plastic catheter or metal needle that’s inserted into the skin. Any time the child wants to eat, an additional amount of insulin can be delivered. - Tubeless “pod” pump

A pod pump is attached to the child’s body — often on the belly, hip, upper arm, or thigh — and there’s no tubing. It delivers insulin through a small catheter underneath the pod. Just like a pump with tubing, it dispenses insulin all day and additional “bolus” doses can be given when needed for meals or high blood-sugar levels. They need to be changed every two or three days, but pod pumps provide flexibility for kids and their parents, allowing more spontaneous eating and activities, since insulin doses can be adjusted on the spot. - Continuous glucose monitoring system (CGM)

This measures glucose levels nearly continuously through a sensor with a needle inserted under the skin. The sensor, about the size of a quarter, must be replaced every six or seven days but provides readings every five minutes. A small transmitter is attached to the sensor, which sends info to the pump screen or to a small receiver. The readings indicate whether levels are going up or down; alerts can notify a child (or parent) of these changes. While CGM devices are an incredible advance, they still require that you check blood sugars from the fingertips to calibrate the device and for insulin dosing, says Dr. Laffel. The goal for the future, she adds, is an artificial pancreas, where the CGM along with a pump or pod will automatically determine the insulin doses.